|

By Laurie Venter

Written for the SA RR Club Magazine in about the late 1980’s when there was, once again, a push to completely eliminate the white from the RR’s. She is talking about a previous time this topic came up. At that time white was still quite prevalent and most breeders were doing their best to bred it down to the amount stated in the Standard but some were wanting to do away with it altogether. People are the key factor in breeding plans. Without their egos there wouldn’t be any shows. Long ago Paul said, “Parade all the dogs before a panel of judges and let them rate the dogs as to their individual excellence.” People LIKE to be important. They like to be shown respect. They have huge egos. This is why it is so dangerous to have our beloved breed subject to fashions. Opinions are formed by a strong individual and in expressing these to judges, other fellow colleagues, who ever, …the group is swayed and complies with the dominant party. People LIKE to change the emphasis in the breed standard, and this is what leads to what I term, fashions. It makes them powerful and strokes their egos. Either a new look at the breed will bring about a new direction in trying to produce the `perfect’ animal, or, direct changes will be made to the standard, changing the emphasis of what is needed and what is desirable. Unfortunately they make the changes without having studied the breed, the history of the breed, nor even having done a cursory research into whether this is a good idea or not. Usually they promote what they like and are used to, and this means promoting their dogs. For example the campaign to raise the height of dogs to 30” in the 1970’s. Again and again people try to change the standard. Sometimes they have succeeded. Take the question of WHITE. Take my mother in the 40’s, for example. She wanted an all over colour and so used to drown the pups which had white socks. When I spoke to the Bococks, Jack determinedly selected the one with the white foot, preferably both front feet being white, as his pick of litter. He did this on a number of occasions and so I questioned him as to why this was his preference. “It’s in the breed,” he said. “What’s in the breed,” I asked. “The white,” he replied, looking at me as though I was daft. “You like the white?” I asked. “It’s in the breed”, he said again. “Yes” I said. “But do YOU like the white?” “It’s eye catching.” “How come?’ He opened up, smiling at me. Perhaps my stupidity and determined questioning had amused him. “It’s eye catching when the dog runs into the ring. That lovely red with the flashing white feet looks good.” He reflected, pausing a while. “It’s better for the white to be even. If it’s uneven the dog can look as if it has an uneven gait.” I remembered that he was a judge and had judged dogs in Rhodesia as well as South Africa, and so had seen a lot across the breadth of the land. “How even should it be?” I asked, risking that gentle smile at my silly questions. “Well, two white feet are better than one,” he said. “One white foot can look as if the dog is lame.” He got a far away look in his eyes. “That’s why they decided to stop breeding for white. It was too difficult.” I thought about what he had said. Something was nagging at the back of my brains. “You said it is in the breed.” I nudged him back to the beginning. “Yes.” “What do you mean it is in the breed?” His clear blue eyes looked sharply at me. Suddenly he was serious. He was in his seventies. He loved these dogs, and had had Ridgebacks for many years. He knew and respected the breed. “You must never get rid of the white.” He stared at me, anxious, trying to make me understand something important. “Why not?” “Because the best dogs all had white.” “Best…in what way?” I asked. “You watch,” he said. “The one with the white is independent. He’s a thinker. I’ve seen it again and again.” Ah. So white was linked to character. Good character. Excellent character, in fact. Tom Hawley tackled me on the same subject. He was staying with us. A symposium was being held in Pretoria. He had not been invited and of all the South African breeders, who had contributed extensively to the breed, he had perhaps advertised Ridgebacks world wide, more than anyone else had had. Not to invite him and his dear wife Blackie to the symposium made a laugh of the whole affair. I contacted them and they were only too happy to come up from Aliwal North to attend. While walking around the farm and looking at the dogs he also adamantly declared that white were not to be eliminated from the breed. “It’s a part of the breed.” He echoed the conversation I had had with Jack Bocock. I told him how mother would drown the puppies, which had white feet. His face wrinkled in distaste. “Pity,” he said. “A lot of good dogs had white on them.” He pointed half way up his arm. “Kim of Houndscroft had white up his front leg.” I was startled. This dog appeared on the pedigrees. It showed how little I knew. “It’s not dominant,” Tom said. “White is not dominant.” He looked at me and jutted out his chin, as if daring me to contradict him. “He was a great stud,” he said. “A great stud.” “Did he have a lot of puppies?” “He was an excellent dog. Tall. He had a hard character. Well muscled.” But he was warned that if white was allowed without restriction then the chest blaze would be enlarged and would creep up the neck and leak down the upper arms, and the white on the feet would rise farther and farther up the leg. He warned that in the end the RR would look like a Boxer with a ridge. I thought about this huge piece of information I had been given. “The white was on a lot of good dogs. Kim of Houndscroft…..” He rattled off a lot of names. He looked directly at me. “Don’t ever get rid of the white. It goes with sound temperament.” Here were two great breeders who had implored me not to eliminate white. The third great breeder who helped to change my thinking was Bill Howard of Rockridge kennels. He too stated that white should be kept in the breed. None of these great breeders, however, ever advocated that we should allow more white than the Standard stipulated, nor keep a white soxed dog for breeding or showing. And what do we have with the passing of the years? We have fashions, which have come and gone. These depend on the current viewpoints. The Ridgeback breed is young for this rigid outlook. Think of Salukis and Afghans, where possibly 2000 years have passed and these breeds are still in existence. Right now, in Europe, dogs are being bypassed if the toenails are not all the same colour. What a strange thing to limit one’s breeding stock for so ridiculous a `fault’. This surely is a trend, a fashion, where a deliberate selection for minor issues can only bring in negative qualities over a period of time. When dogs get eliminated from breeding use, this narrows the pool of genes. We play god and change the breed by our selection and ordaining of the future matings.

0 Comments

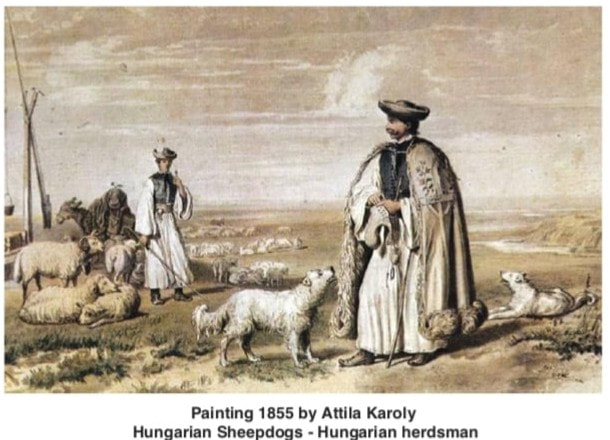

BY Wayne R Cavanaugh “That judge doesn’t know the breed standard!” It’s a common declaration heard around the rings, a slightly angry statement, an editorial comment. When I hear it, I can’t help but think about what “knowing” a breed standard really means. If knowing the breed standard means reading and memorizing its words, it would be an elementary task. I can’t imagine that anyone would see a perfect score on a breed standard test as proper verification of breed knowledge. Yes, it’s part of the learning journey, but on their own, breed standards aren’t enough in a real quest for knowledge. The official requirements are: to memorize the breed standard, take a test, attend a seminar, get the certificate, find a mentor, and visit a breeder. While those are reasonable learning elements, they alone cannot make anyone an expert. First, the focus is on getting answers instead of learning how to ask ourselves the larger questions. Second, it means applying the standard to the current dogs at hand. Third, it understandably runs the risk of perpetuating someone else’s interpretation of the breed standard. While that can be a great interpretation, it can also just be a snapshot in time. The style of the day lives on, and we’ve explored nothing in depth about the core development of the breed. Gaining actual breed knowledge means going beyond the typical requirements. We must find ways to ask ourselves questions, even without answers, to create our own master tools instead of relying on the beginner’s set. It’s necessary to learn from the knowledge of others, but without finding other ways to seek our own answers, we won’t be able to see the standards come alive on the page and in the ring. My approach to learning has obvious personal biases and is sure to be incomplete to all and incomprehensible to some. I hope it sparks an interest in diving deeper into thinking, learning, and seeing things differently. Origin and Function While the standard may be the blueprint, nothing can be built without a sound foundation of origin, history, and function. The typical approach is to take the time to read the preambles in breed standards, on breed club websites, and in dog books. Learning from reading, however, is incomplete unless we simultaneously consider how each sentence relates to each and every specific part of the breed’s conformation, movement and temperament. It’s the “why” that’s important. For example, reading that function in a breed requires a long, deep muzzle offers zero references to the actual size and proportions of the muzzle. How long and how deep? And most important, why? If, for example, the breed’s function is to point and retrieve a pheasant, we need to know and consider the size of the pheasant. I’ll save you that step. The typical male ring-necked pheasant in the United States is 2.6 pounds and 3.5 feet long. The common pheasant in the UK is about the same length but dense at 3.3 pounds. Proportionally, for a 200-pound human, that’s similar to carrying a 10-pound, 3-foot-long bag of wet concrete by the teeth. Thinking about these seemingly inconsequential facts is the only way to ingrain in your brain the image of proper muzzle size and shape, other associated head elements, neck, shoulders and supporting front assemblies required to carry that particular game bird over distance. It is clearly not by basing proportions by the dogs in the ring which all may be wrong! Another example is whether a sighthound breed requires large round feet with thick pads for long distances in the sand? Find out why and how that relates to the function of other foot shapes. Related Breeds There is no better way to never learn about a breed than to study only that breed. Learning about the "related breeds," the family of breeds in which a breed exists, is key to understanding relative breed proportions. At the end of the day, it really is all relative. The English Springer Spaniel is described as the tallest and raciest of land spaniels. Beyond just measurements, knowing how tall and racy they should be required learning about the breeds in that extended family, their size and mass, and what makes each of them unique. You need to learn about English Toy Spaniels to learn about Cavaliers. And if you don't learn about Great Danes and Scottish Deerhounds, you may never understand the correct shape and outline of the Irish Wolfhound. Irish Wolfhounds are sighthounds, a massive rough-coated greyhound, and should have an outline to reflect that heritage. Yet, we still see judges award Irish Wolfhounds with Great Dane outlines. We need to learn about the related breeds to know the specifics of any breed. At the storied AKC Sesquicentennial Show in 1926, five dogs were entered as "Retrievers." Since then, six distinct retriever breeds have evolved. At the same show, spaniels were divided into Clumber, Cocker, Field, Irish Water, Springer, and Sussex. Still, there were no distinctions for English and Welsh Springers or American and English Cockers. Anyone studying those breeds should learn how, when and why they evolved before learning about any of them. What exactly sets each apart, and how does that relate to origin and function? Root Breeds "Root breeds" can be largely described as the crosses used to create a breed. Sorry, but the Ark didn't pull up to Crufts in 1891 and deposit all purebred breeds as we know them today. When we see uniformity within a breed today, it's easy to forget that over 80% of today's breeds are less than 120 years old. All breeds have root breeds. Our job is to learn what they are, what they contributed and why, and how much of those traits we want or don't wish to in today's breeds. Learning about root breeds also gives perspective into a breed's anatomical history. Learning to see a breed's anatomy while picturing its root breeds offers a unique insight into breed history and how a breed was developed. For example, pointer development likely included early infusions of foxhound and bloodhound for scenting, greyhound for speed and agility, and the occasional dash of white bull terrier for tenacity. Those root breeds only sometimes look today like they did a century ago when they were blended in, so further history homework is required. Meanwhile, consider the pointer's underline. The standard says, "tuck-up should be apparent but not exaggerated". On its own, that doesn't explain a thing. Apparent? How apparent? Exaggerated compared to what? The key to those answers is embedded in learning about the root breeds. Only then can we understand that too much tuck-up indicates too much greyhound, and straight, skirted underlines indicate too much scent hound. With that knowledge, we have specific and proportional information about what "not exaggerated" means at both ends of the spectrum. Old Art

If you look at old prints by great dog artists, including Edmund Osthaus, Arthur Wardle, John Emms, Leon Danchin, Maud Earl and later, Boris Riab, you'll see that they all seriously studied the breeds and not just the individual dogs they drew and painted. They went beyond conformation. They masterfully folded the breed's temperament, intensity, and action into a vivid still image. Sometimes you'll see some forms of exaggeration for specific features, especially heads and tails. Our chance to ask them why has long passed, but I've always suspected they focused on unique breed traits, a subtle reminder of the elements of breed type. Old art is a fascinating way to trace a breed's development. We can see the breeds before they were developed into more specific breeds within the family of breeds. If you ask which setter, for example, is portrayed in an old painting, the answer may be none in particular. It was just a setter, the predecessor to the four setter breeds. The best artists were hired by patrons to paint their own dogs. Accordingly, many great paintings from the 1800s are of hunting and toy breeds owned by wealthy sportsmen and women of the Victorian era (1837-1901). Consequently, a spectacular representation of hunting and toy breeds exists as a treasure trove from which to learn. Art from the Victorian era is particularly interesting as a timeline of development. Many beautiful clues from the past are embedded in each pencil line or brush stroke. Old Photographs Following the great art of the mid-18th to mid-19th century came classic photographs of the 20th century. Photos from old catalogues, old dog magazines, and online are a great way to explore the reality of the day. One of the most accessible photo collections is the Best in Show and group winners from Westminster and Crufts. As I've mentioned before, all of these dogs were judged to be excellent examples of the same breed standards we use today. You'll have to be the judge of which one meets your interpretation of the standard. Then, sit back and consider what the writers of the original breed standards intended the breeds to look like. Consider what they might think of the dogs today. While there is no right or wrong, putting ourselves in their shoes is an interesting and often sobering experience. Geographical Differences While there are other excellent approaches to learning - for example, seeing dogs do their jobs and seeing how some breeds reflect the fashions of the day – one more to consider is geographical differences. This is a slippery slope in some breeds but necessary to consider, even if you disagree. If you haven't seen the breeds you're studying in their country of origin or in different unassociated countries, you'll miss a chance to fill in some gaping blanks. What are the essential differences between winning dogs from our country and the country of origin? What elements may have shaped these differences? Asking which is better is not the point. It's a matter of learning by seeing and understanding the differences and drawing our own conclusions. Summary To think that we know a breed standard by honing our ability to identify dogs that look like dogs that are winning today is total folly. First, it's not difficult to point to dogs that look like the winners of the day, but doing so can quickly turn a breed into a cartoon of itself. There is no better way to lose perspective of a breed than to think that the dogs before us are the only ones that ever existed. The only way to learn is to go far beyond what we see in the ring. We must learn to ask ourselves essential and sometimes difficult questions from the past and present before we can learn to see the whole dog, the sum of its parts, the essence of the breed. We need to discover new approaches to learning and question how best to apply those approaches to avoid becoming bandwagon judges following the trends of the day instead of blazing the future by learning from the past. |

AuthorLela Trescec & Maja Kljaic Archives

June 2023

Categories |

|

UZGAJIVAČNICA RODEZIJSKIH RIĐBEKA

RHODESIAN RIDGEBACK KENNEL NEOMELE ul.1.maja 70 Reka, 48 000 Koprivnica CROATIA |

ⓒ 2024 NEOMELE - RHODESIAN RIDGEBACKS

All content and data on this website is protected by copyright.

No part of this website may be used, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from

Neomele kennel/Maja Kljaic & Lela Trescec.

All content and data on this website is protected by copyright.

No part of this website may be used, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from

Neomele kennel/Maja Kljaic & Lela Trescec.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed