|

BY Wayne R Cavanaugh “That judge doesn’t know the breed standard!” It’s a common declaration heard around the rings, a slightly angry statement, an editorial comment. When I hear it, I can’t help but think about what “knowing” a breed standard really means. If knowing the breed standard means reading and memorizing its words, it would be an elementary task. I can’t imagine that anyone would see a perfect score on a breed standard test as proper verification of breed knowledge. Yes, it’s part of the learning journey, but on their own, breed standards aren’t enough in a real quest for knowledge. The official requirements are: to memorize the breed standard, take a test, attend a seminar, get the certificate, find a mentor, and visit a breeder. While those are reasonable learning elements, they alone cannot make anyone an expert. First, the focus is on getting answers instead of learning how to ask ourselves the larger questions. Second, it means applying the standard to the current dogs at hand. Third, it understandably runs the risk of perpetuating someone else’s interpretation of the breed standard. While that can be a great interpretation, it can also just be a snapshot in time. The style of the day lives on, and we’ve explored nothing in depth about the core development of the breed. Gaining actual breed knowledge means going beyond the typical requirements. We must find ways to ask ourselves questions, even without answers, to create our own master tools instead of relying on the beginner’s set. It’s necessary to learn from the knowledge of others, but without finding other ways to seek our own answers, we won’t be able to see the standards come alive on the page and in the ring. My approach to learning has obvious personal biases and is sure to be incomplete to all and incomprehensible to some. I hope it sparks an interest in diving deeper into thinking, learning, and seeing things differently. Origin and Function While the standard may be the blueprint, nothing can be built without a sound foundation of origin, history, and function. The typical approach is to take the time to read the preambles in breed standards, on breed club websites, and in dog books. Learning from reading, however, is incomplete unless we simultaneously consider how each sentence relates to each and every specific part of the breed’s conformation, movement and temperament. It’s the “why” that’s important. For example, reading that function in a breed requires a long, deep muzzle offers zero references to the actual size and proportions of the muzzle. How long and how deep? And most important, why? If, for example, the breed’s function is to point and retrieve a pheasant, we need to know and consider the size of the pheasant. I’ll save you that step. The typical male ring-necked pheasant in the United States is 2.6 pounds and 3.5 feet long. The common pheasant in the UK is about the same length but dense at 3.3 pounds. Proportionally, for a 200-pound human, that’s similar to carrying a 10-pound, 3-foot-long bag of wet concrete by the teeth. Thinking about these seemingly inconsequential facts is the only way to ingrain in your brain the image of proper muzzle size and shape, other associated head elements, neck, shoulders and supporting front assemblies required to carry that particular game bird over distance. It is clearly not by basing proportions by the dogs in the ring which all may be wrong! Another example is whether a sighthound breed requires large round feet with thick pads for long distances in the sand? Find out why and how that relates to the function of other foot shapes. Related Breeds There is no better way to never learn about a breed than to study only that breed. Learning about the "related breeds," the family of breeds in which a breed exists, is key to understanding relative breed proportions. At the end of the day, it really is all relative. The English Springer Spaniel is described as the tallest and raciest of land spaniels. Beyond just measurements, knowing how tall and racy they should be required learning about the breeds in that extended family, their size and mass, and what makes each of them unique. You need to learn about English Toy Spaniels to learn about Cavaliers. And if you don't learn about Great Danes and Scottish Deerhounds, you may never understand the correct shape and outline of the Irish Wolfhound. Irish Wolfhounds are sighthounds, a massive rough-coated greyhound, and should have an outline to reflect that heritage. Yet, we still see judges award Irish Wolfhounds with Great Dane outlines. We need to learn about the related breeds to know the specifics of any breed. At the storied AKC Sesquicentennial Show in 1926, five dogs were entered as "Retrievers." Since then, six distinct retriever breeds have evolved. At the same show, spaniels were divided into Clumber, Cocker, Field, Irish Water, Springer, and Sussex. Still, there were no distinctions for English and Welsh Springers or American and English Cockers. Anyone studying those breeds should learn how, when and why they evolved before learning about any of them. What exactly sets each apart, and how does that relate to origin and function? Root Breeds "Root breeds" can be largely described as the crosses used to create a breed. Sorry, but the Ark didn't pull up to Crufts in 1891 and deposit all purebred breeds as we know them today. When we see uniformity within a breed today, it's easy to forget that over 80% of today's breeds are less than 120 years old. All breeds have root breeds. Our job is to learn what they are, what they contributed and why, and how much of those traits we want or don't wish to in today's breeds. Learning about root breeds also gives perspective into a breed's anatomical history. Learning to see a breed's anatomy while picturing its root breeds offers a unique insight into breed history and how a breed was developed. For example, pointer development likely included early infusions of foxhound and bloodhound for scenting, greyhound for speed and agility, and the occasional dash of white bull terrier for tenacity. Those root breeds only sometimes look today like they did a century ago when they were blended in, so further history homework is required. Meanwhile, consider the pointer's underline. The standard says, "tuck-up should be apparent but not exaggerated". On its own, that doesn't explain a thing. Apparent? How apparent? Exaggerated compared to what? The key to those answers is embedded in learning about the root breeds. Only then can we understand that too much tuck-up indicates too much greyhound, and straight, skirted underlines indicate too much scent hound. With that knowledge, we have specific and proportional information about what "not exaggerated" means at both ends of the spectrum. Old Art

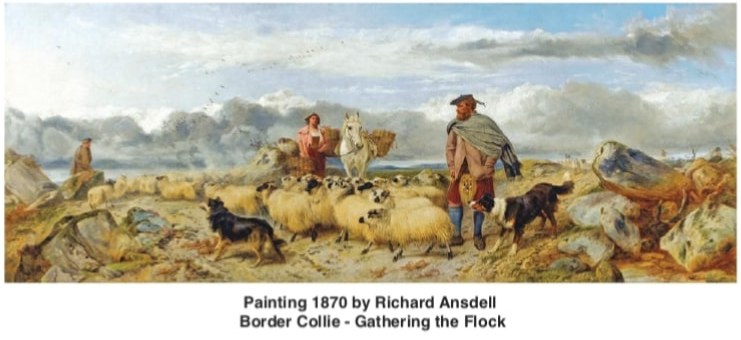

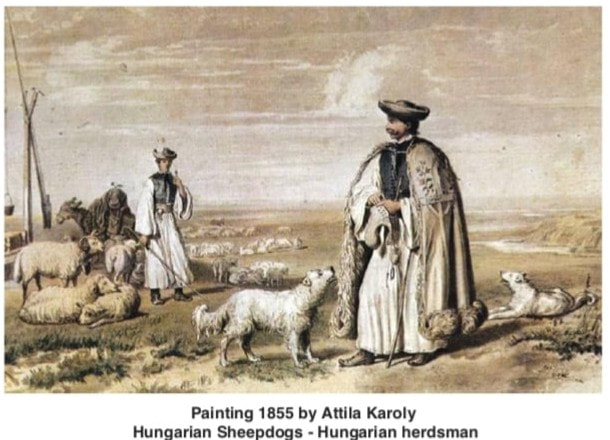

If you look at old prints by great dog artists, including Edmund Osthaus, Arthur Wardle, John Emms, Leon Danchin, Maud Earl and later, Boris Riab, you'll see that they all seriously studied the breeds and not just the individual dogs they drew and painted. They went beyond conformation. They masterfully folded the breed's temperament, intensity, and action into a vivid still image. Sometimes you'll see some forms of exaggeration for specific features, especially heads and tails. Our chance to ask them why has long passed, but I've always suspected they focused on unique breed traits, a subtle reminder of the elements of breed type. Old art is a fascinating way to trace a breed's development. We can see the breeds before they were developed into more specific breeds within the family of breeds. If you ask which setter, for example, is portrayed in an old painting, the answer may be none in particular. It was just a setter, the predecessor to the four setter breeds. The best artists were hired by patrons to paint their own dogs. Accordingly, many great paintings from the 1800s are of hunting and toy breeds owned by wealthy sportsmen and women of the Victorian era (1837-1901). Consequently, a spectacular representation of hunting and toy breeds exists as a treasure trove from which to learn. Art from the Victorian era is particularly interesting as a timeline of development. Many beautiful clues from the past are embedded in each pencil line or brush stroke. Old Photographs Following the great art of the mid-18th to mid-19th century came classic photographs of the 20th century. Photos from old catalogues, old dog magazines, and online are a great way to explore the reality of the day. One of the most accessible photo collections is the Best in Show and group winners from Westminster and Crufts. As I've mentioned before, all of these dogs were judged to be excellent examples of the same breed standards we use today. You'll have to be the judge of which one meets your interpretation of the standard. Then, sit back and consider what the writers of the original breed standards intended the breeds to look like. Consider what they might think of the dogs today. While there is no right or wrong, putting ourselves in their shoes is an interesting and often sobering experience. Geographical Differences While there are other excellent approaches to learning - for example, seeing dogs do their jobs and seeing how some breeds reflect the fashions of the day – one more to consider is geographical differences. This is a slippery slope in some breeds but necessary to consider, even if you disagree. If you haven't seen the breeds you're studying in their country of origin or in different unassociated countries, you'll miss a chance to fill in some gaping blanks. What are the essential differences between winning dogs from our country and the country of origin? What elements may have shaped these differences? Asking which is better is not the point. It's a matter of learning by seeing and understanding the differences and drawing our own conclusions. Summary To think that we know a breed standard by honing our ability to identify dogs that look like dogs that are winning today is total folly. First, it's not difficult to point to dogs that look like the winners of the day, but doing so can quickly turn a breed into a cartoon of itself. There is no better way to lose perspective of a breed than to think that the dogs before us are the only ones that ever existed. The only way to learn is to go far beyond what we see in the ring. We must learn to ask ourselves essential and sometimes difficult questions from the past and present before we can learn to see the whole dog, the sum of its parts, the essence of the breed. We need to discover new approaches to learning and question how best to apply those approaches to avoid becoming bandwagon judges following the trends of the day instead of blazing the future by learning from the past.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLela Trescec & Maja Kljaic Archives

June 2023

Categories |

|

UZGAJIVAČNICA RODEZIJSKIH RIĐBEKA

RHODESIAN RIDGEBACK KENNEL NEOMELE ul.1.maja 70 Reka, 48 000 Koprivnica CROATIA |

ⓒ 2024 NEOMELE - RHODESIAN RIDGEBACKS

All content and data on this website is protected by copyright.

No part of this website may be used, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from

Neomele kennel/Maja Kljaic & Lela Trescec.

All content and data on this website is protected by copyright.

No part of this website may be used, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from

Neomele kennel/Maja Kljaic & Lela Trescec.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed